Care as Infrastructure: The Hidden Labour of the Miners’ Strike

While history remembers the picket lines, the clashes with police, Arthur Scargill, and the National Union of Mineworkers, little has been done to understand the activism carried out by women and the LGBT community and the deeper union built through unpaid labour, compassion, and care.

The Women Who Held the Line

While the headlines centred on confrontation, women were organising on the ground. The National Women Against Pit Closures (NWAPC) took on the vital work of keeping communities going: running kitchens, distributing essential supplies, coordinating fundraising, hosting meetings, and building networks of support across the country. They wrote articles and pamphlets, promoted the cause through the press, and travelled across the UK to connect with other activist groups.

Many were new to activism, though some brought experience from earlier movements like Women’s Liberation and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Their contribution was crucial to the strike’s endurance. While the government and press painted miners as violent and unreasonable, these women led with solidarity and care. Their resistance made fewer headlines but it kept people fed, connected, and committed.

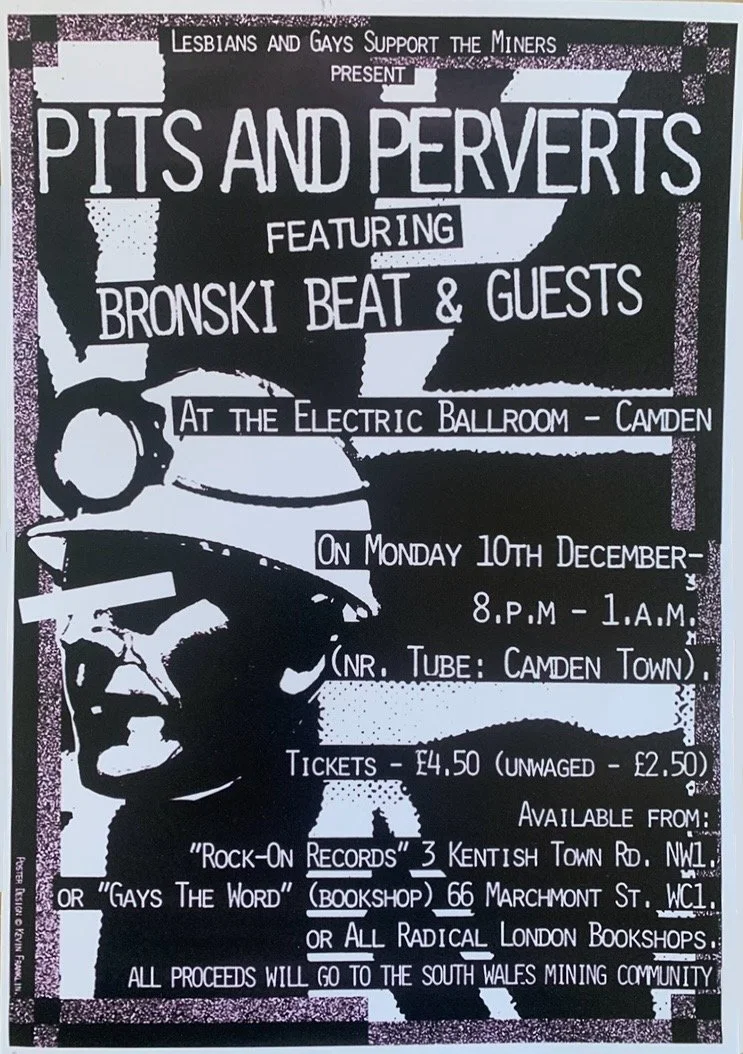

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), too, played a critical part in this care infrastructure. Through benefit gigs, drag nights, and tireless organising, queer activists not only raised money but built something even more valuable: solidarity across difference. In a time when both groups were demonised, they chose to stand side by side. That choice would ripple far beyond the strike, helping to shift the Labour Party’s stance on LGBTQ+ rights and forging a political alliance that still endures….well, just about.

The Care Work Capitalism Tries to Forget

The kind of labour these women and queer communities carried out wasn’t new. Before industrial capitalism, women’s work was deeply interwoven into daily life and community survival. In pre-capitalist societies, tasks like farming, healing, weaving, and raising children were part of a shared economy of survival. There wasn’t the same divide between “home” and “work”; all labour was necessary, and all of it was visible.

That changed with the rise of industrial capitalism. Work was redefined as something that could be measured, timed, and sold. Labour that generated profit, typically men’s labour, became “productive.” Women’s labour was pushed into the background and recast as natural instinct, moral duty, or love. The more tightly work became tied to profit, the easier it became to dismiss anything that didn’t fit that model. Women’s labour didn’t just go unpaid, it was made invisible by design.

Wages for Housework: Making the Hidden Visible

Not everyone accepted that erasure. Alongside second-wave feminism, a different kind of feminist politics was emerging, one that looked beyond the workplace and into the home. The Wages for Housework movement, led by figures like Silvia Federici and Selma James, argued that domestic labour, childcare, and emotional support were not just personal responsibilities. They were economic foundations.

The demand for wages wasn’t simply about getting paid. It was a political strategy to expose the exploitation baked into capitalism, to make visible the invisible work that sustains everything else. While second-wave feminism often focused on gaining access to male-dominated workplaces, Wages for Housework recognised that many women, especially working-class women and women of colour, were already working double or triple shifts, both paid and unpaid.

Second-wave feminists often assumed that access to employment would naturally rebalance domestic responsibilities. In hindsight, that feels like naive, wishful thinking and an indicator that second-wave feminism didn’t speak to the realities of all women’s lives.

Resistance Relies on Care

Although largely unrecognised, the politics of care was central to the Miners’ Strike. It serves as another example of whose labour is valued, and whose is relied upon but ignored. The strike should be remembered as more than a fight over jobs. It was a fight over how we care for each other. Women and queer communities embodied that care with fierce resolve, not as an afterthought, but as the core of collective survival.

But in a world that refuses to see care as valuable, it takes very little effort to hide it. And when it’s hidden, it’s easily devalued, ignored, or written out of the story.

Care is not sentimental. It is not secondary. It is infrastructure. And every movement that has endured, every strike that has lasted longer than the state expected, has done so because someone was organising rotas, sourcing food donations, writing leaflets, setting up chairs, listening and connecting.

This isn’t just history, it is a reminder. In a time of rising inequality, broken public services, and overlapping crises, it’s clear that, as Grace Blakeley puts it, “no one is coming to save us. We have to save ourselves.” That means people showing up for one another, communities coming together across difference, and collective struggle rooted in care. We need to move away from capitalist individualism and the myth of political heroes and villains, towards a politics of shared responsibility, mutual support, and collective power.