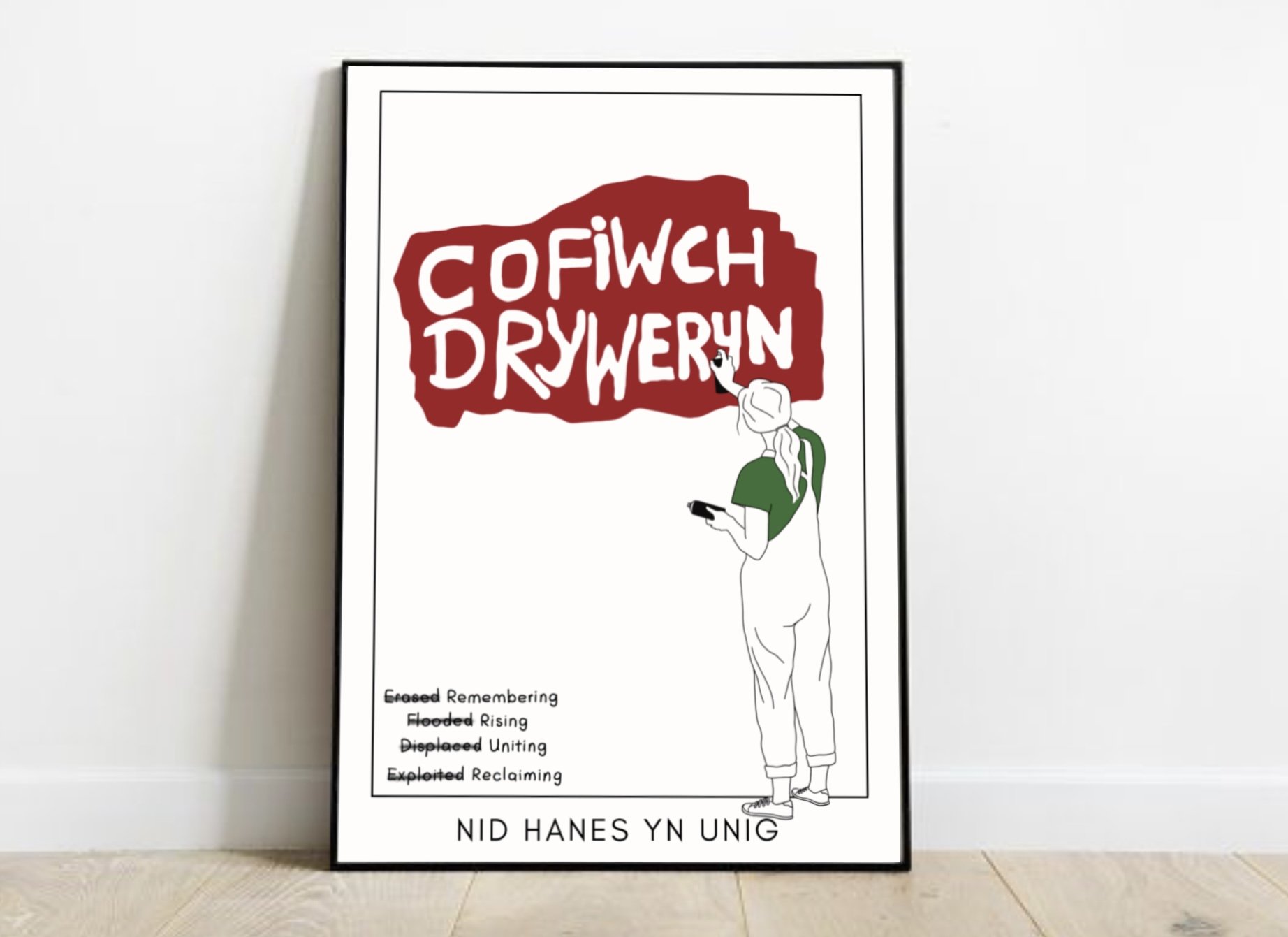

Cofiwch Dryweryn

The story is well documented, so I’ll keep the background brief.

In 1965, despite fierce resistance, the village of Capel Celyn in the Tryweryn Valley was subsumed by 70 billion litres of water. The valley was flooded to create a reservoir intended to supply drinking water to the people of Liverpool. Except that wasn’t entirely true — much of the water was later sold to private companies, who essentially profited from the displacement and destruction of land and community.

This wasn’t the first time Wales had been exploited in this way. The creation of the Elan Valley reservoirs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw over a hundred people forcibly displaced, with homes and farms destroyed to supply water to Birmingham.

Against this backdrop, Cofiwch Dryweryn, created by Meic Stephens, has become one of the most recognisable pieces of protest art in Wales. Painted on the ruins of a house along the A487 outside Aberystwyth, it’s a powerful symbol that tells us to remember. But I wonder if it’s now too often seen more as a commemorative slogan than a call to action. Its original purpose was more urgent — not just remembrance, but resistance. A call to stay alert, stay angry, and keep the flame of protest alive.

I think I was guilty of seeing it this way — or worse, of not thinking about it at all. It’s taken me far too long to begin understanding the scale of violence and exploitation inflicted on Wales by England. Yes, I had a rudimentary understanding of things like the Blue Books, the Rebecca Riots, the Miners’ Strikes, but I hadn’t joined the dots. I hadn’t really stopped to think that this relationship, built on extraction, suppression and imbalance, isn’t just history. It is still happening.

And it happens in more subtle, everyday ways, too. I think the legacy of centuries of messaging, that Wales and its people are somehow lesser, wild, backward, or barbaric, still persists, both subtly and overtly. It shows up in ways that aren’t always easy to spot: in the blurring of Welsh and British identity, in the celebration of the royal family, in the flying of Union Jacks. It takes its toll. You can see echoes of it in the historical willingness to abandon the Welsh language during the industrial revolution, and in the fear some parents still carry, that sending their children to a Welsh-medium school is ‘pointless’ and might somehow hold them back in life.

I’m still learning, and I’ve got a long way to go. But one recent example that brought things into sharper focus for me is the ongoing HS2 rail project, which has long been classified as an “England and Wales” scheme. This classification means that, unlike Scotland and Northern Ireland, Wales doesn’t receive any additional funding to compensate for a project that offers no direct benefit. In fact, Welsh taxpayers are helping to fund infrastructure that doesn’t serve them.

I saw a post recently by journalist Will Hayward highlighting comments from the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, who said Wales should “be a little bit more grateful”. He was referring to the £445 million it had been allocated to Wales for rail improvements. But that figure, spread over ten years, doesn’t come close to what’s been lost. The Welsh Government estimates that Wales will miss out on around £800 million in investment over the next decade because of the continued insistence on classifying HS2 as an England and Wales project.

I wanted to share where I’m at with this as a kind of apology — to some of the people in my life (who probably won’t read this, but that’s okay) for not getting here sooner. For the times I didn’t question what should have been questioned. Microaggressions, subtle bias, quiet assumptions dressed up as truth — it’s easy to absorb these things without even realising it. The quieter, more insidious messaging is often the most powerful, and the most dangerous. Learning to ask myself: Do I really believe this? Who benefits from me believing this? And what is the bigger picture? — it’s been a slower process than it probably should have been. But I’m so here now.

Whether you see yourself as more British than Welsh and feel pride at the sight of a Union Jack, or believe Wales should be independent and would vote for it tomorrow — the fundamental truth remains: Wales has been repeatedly exploited, sidelined, and forgotten. Its resources and expertise are consistently extracted, while very little is returned. That’s why Cofiwch Dryweryn is still so important — it should light a fire within us, not just a candle of remembrance for the past.